What is in a Russian hut drawings. Peasant furniture and utensils

Housing is as big as an elbow, and living is as big as a nail

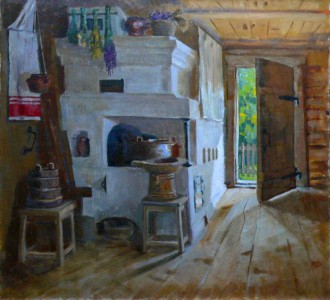

The interior of a peasant home, which can be found in our time, has evolved over the centuries. Due to limited space, the layout of the house was very rational. So, we open the door, bending down, we enter...

The door leading to the hut was made low with a raised threshold, which contributed to greater heat retention in the house. In addition, the guest, entering the hut, willy-nilly had to bow to the owners and the icons in the red corner - a mandatory attribute of a peasant hut.

Fundamental when planning the hut was the location of the stove. The stove played the most important role in the house, and the very name “izba” comes from the Old Russian “istba, istobka”, that is, to heat, to heat.

The Russian stove fed, warmed, treated, they slept on it, and some even washed in it. Respectful attitude towards the stove was expressed in proverbs and sayings: “The stove is our dear mother”, “The whole red summer is on the stove”, “It’s like warming up on the stove”, “Both years and years - one place - the stove.” Russian riddles ask: “What can’t you get out of the hut?”, “What can’t be seen in the hut?” - warmth.

![]() In the central regions of Russia, the stove usually stood in the right corner of the entrance. Such a hut was called a “spinner”. If the stove was located to the left of the entrance, then the hut was called “non-spinner”. The fact is that opposite the stove, on the long side of the house, there was always a so-called “long” bench where women spun. And depending on the location of this shop in relation to the window and its illumination, the convenience for spinning, the huts were called “spinners” and “non-spinners”: “Do not spin by hand: the right hand is to the wall and not to the light.”

In the central regions of Russia, the stove usually stood in the right corner of the entrance. Such a hut was called a “spinner”. If the stove was located to the left of the entrance, then the hut was called “non-spinner”. The fact is that opposite the stove, on the long side of the house, there was always a so-called “long” bench where women spun. And depending on the location of this shop in relation to the window and its illumination, the convenience for spinning, the huts were called “spinners” and “non-spinners”: “Do not spin by hand: the right hand is to the wall and not to the light.”

Often, to maintain the shape of an adobe hut, vertical “stove pillars” were placed in its corners. One of them, which faced the center of the hut, was always installed. Wide beams hewn from oak or pine were thrown from it to the side front wall. Because they were always black with soot, they were called Voronets. They were located at the height of human growth. “Yaga is standing, with horns on his forehead,” they asked a riddle about the Voronets. The one of the voronets that lined the long side wall was called the “ward beam.” The second ravine, which ran from the stove pillar to the front facade wall, was called the “closet, cake beam.” It was used by the hostess as a shelf for dishes. Thus, both Voronets marked the boundaries functional zones huts, or corners: on one side of the entrance to the stove and cooking (woman's) kuta (corners), on the other - the master's (ward) kuta, and the red, or large, top corner with icons and table. The old saying, “A hut is not red in its corners, but red in its pies,” confirms the division of the hut into “corners” of different meanings.

The back corner (at the front door) has been masculine since ancient times. There was a konik here - a short, wide bench built along the back wall of the hut. Konik had the shape of a box with a hinged flat lid. The bunk was separated from the door (to prevent it from blowing at night) by a vertical board-back, which was often shaped like a horse's head. It was workplace men. Here they wove bast shoes, baskets, repaired horse harnesses, did carving, etc. Tools were stored in a box under the bunk. It was indecent for a woman to sit on a bunk.

The back corner (at the front door) has been masculine since ancient times. There was a konik here - a short, wide bench built along the back wall of the hut. Konik had the shape of a box with a hinged flat lid. The bunk was separated from the door (to prevent it from blowing at night) by a vertical board-back, which was often shaped like a horse's head. It was workplace men. Here they wove bast shoes, baskets, repaired horse harnesses, did carving, etc. Tools were stored in a box under the bunk. It was indecent for a woman to sit on a bunk.

This corner was also called the plate corner, because. here, right above the door, under the ceiling, near the stove, special floorings were installed - floors. One edge of the floor is cut into the wall, and the other rests on a floor beam. They slept on the floorboards, climbing into them from the stove. Here flax, hemp, splinter were dried, and bedding was put away there for the day. Polati was the children's favorite place, because... from their height one could observe everything that was happening in the hut, especially during holidays: weddings, gatherings, festivities.

Any good person could enter the underpass without asking. Without knocking on the door, but for the plated beam the guest, at his will, is not allowed to go. Waiting for an invitation from the hosts to enter the next quarter - red at low levels was extremely inconvenient.

The woman's or stove corner is the kingdom of the female housewife of the "big lady". Here, right at the window (near the light) opposite the mouth of the furnace, hand millstones (two large flat stones) were always placed, so the corner was also called “millstone”. A wide bench ran along the wall from the stove to the front windows; sometimes there was a small table on which hot bread was laid out. There were observers hanging on the wall - shelves for dishes. There were various utensils on the shelves: wooden dishes, cups and spoons, clay bowls and pots, iron frying pans. On the benches and floor there are milk dishes (lids, jugs), cast iron, buckets, tubs. Sometimes there were copper and tin utensils.

The woman's or stove corner is the kingdom of the female housewife of the "big lady". Here, right at the window (near the light) opposite the mouth of the furnace, hand millstones (two large flat stones) were always placed, so the corner was also called “millstone”. A wide bench ran along the wall from the stove to the front windows; sometimes there was a small table on which hot bread was laid out. There were observers hanging on the wall - shelves for dishes. There were various utensils on the shelves: wooden dishes, cups and spoons, clay bowls and pots, iron frying pans. On the benches and floor there are milk dishes (lids, jugs), cast iron, buckets, tubs. Sometimes there were copper and tin utensils.

In the stove (kutny) corner, women prepared food and rested. Here on time big holidays When many guests gathered, a separate table was set for women. Men could not even go into the stove corner of their own family unless absolutely necessary. The appearance of a stranger there was regarded as gross violation established rules (traditions).

The millstone corner was considered a dirty place, in contrast to the rest of the clean space of the hut. Therefore, the peasants always sought to separate it from the rest of the room with a curtain made of variegated chintz, colored homespun or a wooden partition.

During the entire matchmaking, the future bride had to listen to the conversation from the woman's corner. She also came out from there during the show. There she awaited the arrival of the groom on the wedding day. And going out from there to the red corner was perceived as leaving home, saying goodbye to it.

A daughter in a cradle - a dowry in a box.

In the woman's corner there is a cradle hanging on a long pole (chepe). The pole, in turn, is threaded into a ring embedded in the ceiling matrix. In different areas, the cradle is made differently. It can be entirely woven from twigs, it can have a side panel made of bast, or a bottom made of fabric or wicker. And they also call it differently: cradle, shaky, kolyska, kolubalka. A rope loop or wooden pedal was tied to the cradle, which allowed the mother to rock the child without interrupting her work. The hanging position of the cradle is typical for Eastern Slavs– Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians. And this is due not only to convenience, but above all to folk beliefs(the cradle standing on the floor appears much later). According to the peasants, the separation of the child from the floor, the “bottom,” contributed to the preservation of vitality, because the floor was perceived as the border between the human world and the underground, where the “evil spirit” lives - the brownie, dead relatives, ghosts. In order to protect the child from evil spirits, sharp objects were placed under the cradle: a knife, scissors, a broom, etc.

Front door, central part The hut had a red corner. The red corner, like the stove, was an important landmark in the interior space of the hut.

Front door, central part The hut had a red corner. The red corner, like the stove, was an important landmark in the interior space of the hut.

No matter how the stove was located in the hut, the red corner was always located diagonally from it. The red corner was always well lit, since windows were cut into both walls making up this corner. He was always facing the sun, i.e. to the south or east. In the very corner, immediately under the shelf, they placed a shrine with icons and a lamp, which is why the corner was also called “holy”. Holy water, consecrated willow and Easter Egg. There was certainly a feather for sweeping icons. It was believed that the icon must stand and not hang. Bills, promissory notes, payment notebooks, etc. were also placed here for the icons.

A curtain or “godnik” was hung on top of the shrine. This was the name given to a specially woven and embroidered narrow, long towel (20-25 cm * 3-4 m). It was decorated along one side and at the ends with embroidery, woven patterns, ribbons, and lace. They hung the god in such a way as to cover the icons from above and from the sides, leaving the faces open.

A refectory consecrated with shrines - that’s what the red corner is. Like a living space Orthodox Christian considered a symbol Orthodox church, and the Red Corner is considered as an analogue of the altar, the most important and honorable place in the house.

There were benches along the walls (front and side) of the red corner. In general, shops were set up along all the walls of the hut. They did not belong to furniture, but were an integral part of the log house and were fixedly attached to the walls. On one side they were cut into the wall, and on the other they were supported by supports cut from boards. A piece of wood decorated with carvings was sewn to the edge of the bench. Such a shop was called pubescent, or “with a canopy,” “with a valance.” They sat on them, slept on them, and stored things. Each shop had its own purpose and name. To the left of the door there was a back or threshold bench. That's what they called it, the konik. Behind it, along the long left side of the hut, from the bunk to the red corner, there was a long shop, different from the others in its length. Like the oven kut, this shop was traditionally considered a women's place. Here they sewed, knitted, spun, embroidered, and did handicrafts. That's why this shop was also called a woman's shop.

Along the front (facade) wall, from the red corner to the stove corner, there was a short bench (aka red, front). Men sat on it during family meals. From the front wall to the stove there was a bench. In winter, chickens were kept under this bench, covered with bars. And finally, behind the stove, to the door, there was a kutna shop. Buckets of water were placed on it.

A table was always placed in the red corner near the converging benches (long and short). The table has always been rectangular in shape with a powerful base. The tabletop was revered as the “palm of God” that gives bread. Therefore, knocking on the table was considered a sin. People used to say: “Bread on the table, so the table is a throne, but not a piece of bread, so the table is a board.”

The table was covered with a tablecloth. IN peasant hut tablecloths were made from homespun, both simple plain weave and made using the technique of bran and multi-shaft weaving. Tablecloths used every day were sewn from two motley panels, usually with a checkered pattern (the colors are very varied) or simply rough canvas. This tablecloth was used to cover the table during lunch, and after eating it was either removed or used to cover the bread left on the table. Holiday tablecloths were different best quality fabrics, such additional details as lace stitching between two panels, tassels, lace or fringe around the perimeter, as well as a pattern on the fabric.

All significant family events took place in the red corner. Here the bride was bought, from here she was taken to the church for the wedding, and at the groom’s house she was immediately taken to the red corner. During the harvest, the first and last sheaves were ceremonially placed in the red corner. During the construction of the hut, if coins were placed under the corners of the first crown for good luck, then the largest one was placed under the red corner. They always tried to especially decorate this corner of the hut and keep it clean. The name “red” itself means “beautiful”, “light”. It is the most honorable place in the house. According to traditional etiquette, a person who came to a hut could only go there at the special invitation of the owners.

Those entering the hut, first of all, turned to the red corner and made the sign of the cross. A Russian proverb says: “The first bow is to God, the second is to the master and mistress, the third is to all good people.”

The place at the table in the red corner under the images was the most honorable: here sat the owner, or the guest of honor. “For a red guest, a red place.” Each family member knew his place at the table. The owner's eldest son sat right hand from the father, the second son is on the left, the third is next to his older brother, etc. “Every cricket knows its nest.” The housewife's place at the table is at the end of the table from the side of the woman's kut and the stove - she is the priestess of the home temple. She communicates with the oven and the fire of the oven, she starts the kneading bowl, puts the dough into the oven, and takes it out transformed into bread.

In addition to benches, the hut had mobile side benches. A place on a bench was considered more prestigious than on a bench; the guest could judge the hosts' attitude towards him depending on this. Where did they sit him - on a bench or on a bench?

The benches were usually covered with a special fabric - shelf cloth. And in general, the entire hut is decorated with home-made items: colored curtains cover the bed and bed on the stove, homespun muslin curtains on the windows, and multi-colored rugs on the floor. The window sills are decorated with geraniums, dear to the peasant’s heart.

Between the wall and the back or side of the stove there was an oven. When located behind the stove, horse harness was stored there; if on the side, then usually kitchen utensils.

On the other side of the stove, next to front door, the cabbage was settling in, - special wooden extension to the stove, along the stairs of which they went down to the basement (underground), where supplies were stored. Golbets also served as a place of rest, especially for the old and small. In some places, the high golbets were replaced by a box - a “trap”, 30 centimeters high from the floor, with a sliding lid, on which one could also sleep. Over time, the descent into the basement moved in front of the mouth of the furnace, and it was possible to get into it through a hole in the floor. The stove corner was considered the habitat of the brownie - the keeper of the hearth.

WITH mid-19th V. In peasant homes, especially among wealthy peasants, a formal living room appears - the upper room. The upper room could have been a summer room; in case of all-season use, it was heated with a Dutch oven. The upper rooms, as a rule, had a more colorful interior than the hut. Chairs, beds, and piles of chests were used in the interior of the upper rooms.

The interior of a peasant house, which has evolved over centuries, represents best example combination of convenience and beauty. There is nothing superfluous here and every thing is in its place, everything is at hand. The main criterion for a peasant house was convenience, so that a person could live, work and relax in it. However, in the construction of the hut one cannot help but see the need for beauty inherent in the Russian people.

In the interior of a Russian hut, the horizontal rhythm of furniture (benches, beds, shelves) dominates. The interior is united by a single material and carpentry techniques. The natural color of the wood was preserved. Presenter color scheme was golden-ocher (the walls of the hut, furniture, dishes, utensils) with the introduction of white and red colors (the towels on the icons were white, the red color sparkled in small spots in clothes, towels, in plants on the windows, in the painting of household utensils).

PEASANT FURNITURE AND Utensils

There was little furniture in the hut, and it did not differ in variety - a table, benches, benches, chests, dish shelves. The wardrobes, chairs, and beds familiar to us appeared in the village only in the 19th century.

TABLE occupied the house important place and served for a daily or holiday meal. The table was treated with respect, called “the palm of God”, giving daily bread. Therefore, it was forbidden to hit the table and for children to climb on it. On weekdays, the table stood without a tablecloth; only bread wrapped in a tablecloth and a salt shaker could be on it. On holidays, it was placed in the middle of the hut, covered with a tablecloth, and decorated with elegant dishes. The table was considered a place where people came together. The person whom the owners invited to the table was considered “one of their own” in the family.

STORE Wood has traditionally served two roles. First of all, they were a help in economic matters and helped to carry out their craft. The second role is aesthetic. Benches decorated with various patterns were placed along the walls of vast rooms. In a Russian hut, benches ran along the walls in a circle, starting from the entrance, and served for sitting, sleeping, and storing household items. Each shop had its own name. The shop near the stove was called Kutnoy, since it was located in the woman’s kut. Buckets of water, pots, cast iron were placed on it, and baked bread was placed on it. Judgment shop went from the stove to the front wall of the house. This shop was higher than the rest. Under it there were sliding doors or a curtain, behind which there were shelves with dishes. Long Shop- a bench that differs from others in its length. It stretched either from the conic to the red corner, along the side wall of the house, or from the red corner along the facade wall. According to tradition, it was considered a women's place where they did spinning, knitting, and sewing. The men's shop was called bunk, like the peasant’s workplace. It was short and wide, shaped like a box with a hinged flat lid or sliding doors where the working tools were stored.

In Russian life, they were also used for sitting or sleeping. BENCHES. Unlike the bench, which was attached to the wall, the bench was portable. It was possible in case of shortage sleeping place place along the bench to increase the space for the bed, or place it next to the table.

Walked under the ceiling POLAVOSHNIKI, on which it was located peasant utensils, and strengthened it near the stove wood flooring – POLATI. They slept in the tents, and during get-togethers or weddings, children climbed in and looked with curiosity at everything that was happening in the hut.

The dishes were stored in SUPPLIERS: These were pillars with numerous shelves between them. On the lower, wider shelves, massive dishes were stored; on the upper, narrower ones, they placed small dishes. Served for storing separate dishes CONSUMER – wooden shelf or open locker. The vessel could have the shape of a closed frame or be open at the top; often its side walls were decorated with carvings or had figured shapes. As a rule, the dishware was located above the ship's bench, under the hand of the mistress.

It was rare that a peasant hut did not have TKATSKY MACHINE, every peasant girl and woman knew how to weave not only simple canvas, but also swearing tablecloths, towels, checkered blankets, deposits for shushpans, chest covers, and bedding.

For a newborn, an elegant dress was hung from the ceiling of the hut on an iron hook. CASSET. Rocking gently, she lulled the baby to the melodious song of a peasant woman.

A constant part of the life of a Russian woman - from youth to old age - was SPINNING WHEELS. An elegant spinning wheel was made by a kind young man for his bride, a husband gave it to his wife as a souvenir, a father gave it to his daughter. Therefore, a lot of warmth was put into its decoration. The spinning wheels were kept throughout life and passed on as a memory of the mother to the next generation.

BOX in the hut he took the place of the guardian of family life. It contained money, a dowry, clothes, and simple household items. Since the most valuable things were kept in it, in several places it was bound with iron strips and locked with locks for strength. The more chests there were in the house, the richer the peasant family was considered. In Rus', two types of chests were common - with a flat hinged lid and a convex one. There were small chests that looked like boxes. The chest was made of wood - oak, less often birch.

While the chest was a luxury item and was used to store expensive things, there was STEST. It was similar in shape to a chest, but made more simply, roughly, and had no decorations. Grain and flour were stored in it and used to sell food at the market.

Peasant utensils

It was difficult to imagine a peasant house without numerous utensils. Utensils are all objects necessary for a person in his everyday life: utensils for preparing, preparing and storing food, serving it on the table; various containers for storing household items and clothing; items for personal hygiene and home hygiene; items for lighting fires, storing and consuming tobacco and for cosmetics.

In the Russian village, mainly wooden and pottery utensils were used. Utensils made from birch bark, woven from twigs, straw, and pine roots were also in widespread use. Some of the wooden items needed in the household were made by the male half of the family. Most of the items were purchased at fairs and markets, especially for cooperage and turning utensils, the manufacture of which required special knowledge and tools.

Previously it was considered the primary item of rural life ROCKER ARM – a thick, arched wooden stick with hooks or notches at the ends. Intended for carrying buckets of water on the shoulders. It was believed that a person had strength as long as he could carry water in buckets on a rocker.

Carrying water on a rocker is a whole ritual. When you go for water, two empty buckets should be in your left hand, and a rocker in your right. The rocker had the shape of an arc. It lay comfortably on the shoulders, and the buckets, placed on the ends of the rocker in specially cut grooves for this purpose, hardly swayed when walking.

OUTRIGGER– massive, curved upward wooden block with a short handle - served not only for threshing flax, but also for beating out linen during washing and rinsing, as well as for bleaching the finished canvas. Rolls were most often made from linden or birch and decorated with triangular-notched carvings and paintings. The most elegant ones were the gift rolls that the boys presented to the girls. Some of them were made in the form of a stylized female figure, others were decorated through holes with beads, pebbles or peas, which made a peculiar “murmuring” sound when working.

The roller was placed in the cradle of a newborn as a talisman, and was also placed under the child’s head during the ritual of the first hair cutting.

RUBEL- a household item that in the old days Russian women used to iron clothes after washing. It was a plate of hardwood with a handle at one end. Transverse rounded scars were cut on one side, the other remained smooth and was sometimes decorated with intricate carvings. Hand-wrung linen was wound on a roller or rolling pin and rolled out with a ruble so that even poorly washed linen became snow-white. Hence the proverb: “Not by washing, but by rolling.” The ruble was made from hardwood: oak, maple, beech, birch, rowan. Sometimes the handle of the ruble was made hollow and peas or other small objects were placed inside so that they would rattle when rolled out.

To store bulky household supplies in cages, barrels, tubs, and baskets were used different sizes and volume.

BARRELS in the old days they were the most common container for both liquids and bulk solids, for example: grain, flour, flax, fish, dried meat, horse meat and various small goods.

For the preparation of pickles, pickles, soaks, kvass, water for future use, for storing flour and cereals they were used TUBES. The necessary accessories for the tub were a circle and a lid. The food placed in the tub was pressed in a circle, and oppression was placed on top. This was done so that the pickles and pickles were always in the brine and did not float to the surface. The lid protected food from dust. The mug and lid had small handles.

TUB– wooden container with two handles. Used for filling and carrying liquid. The tub was used for various purposes. In ancient times, wine was served there during the holiday. In everyday life, water was kept in tubs and brooms were steamed for the bath.

BASH- a round or oblong wooden vessel with low edges, designed for various household needs: for washing clothes, washing dishes, draining water.

GANG- the same tub, but intended for washing in a bathhouse.

For many centuries, the main kitchen vessel in Rus' was POT. The pots could be of different sizes: from a small pot for 200-300 g of porridge to a huge pot that could hold up to 2-3 buckets of water. The shape of the pot did not change throughout its existence and was well suited for cooking in a Russian oven. They were rarely decorated with ornaments. In the peasant house there were about a dozen or more pots of different sizes. They treasured the pots and tried to handle them carefully. If it cracked, it was braided with birch bark and used for storing food.

To serve food on the table, the following tableware was used: DISH. It was usually round or oval in shape, shallow, on a low tray, with wide edges. In peasant life, mainly wooden dishes were common. Dishes intended for holidays were decorated with paintings. They depicted plant shoots, small geometric figures, fantastic animals and birds, fish and skates. The dish was used both in everyday and festive life. On weekdays, fish, meat, porridge, cabbage, cucumbers and other “thick” dishes were served on a platter, eaten after soup or cabbage soup. IN holidays In addition to meat and fish, pancakes, pies, buns, cheesecakes, gingerbreads, nuts, candies and other sweets were served on the platter. In addition, there was a custom to serve guests a glass of wine, mead, mash, vodka or beer on a platter.

Used for drinking intoxicating drinks CHARKOY. It is a small vessel round shape, having a leg and a flat bottom, sometimes there could be a handle and a lid. The glasses were usually painted or decorated with carvings. This vessel was used as an individual vessel for drinking mash, beer, intoxicated mead, and later wine and vodka on holidays.

Charka was most often used in wedding ceremonies. The priest offered a glass of wine to the newlyweds after the wedding. They took turns taking three sips from this glass. Having finished the wine, the husband threw the glass under his feet and trampled it at the same time as his wife, saying: “Let those who begin to sow discord and dislike among us be trampled under our feet.” It was believed that whichever spouse stepped on it first would dominate the family. The owner presented the first glass of vodka at the wedding feast to the sorcerer, who was invited to the wedding as an honored guest in order to save the newlyweds from damage. The sorcerer asked for the second glass himself and only after that began to protect the newlyweds from evil forces.

ENDOVA– a wooden or metal bowl in the shape of a boat with a spout for draining. Used to serve drinks at feasts. The endova was of different sizes: from those that could hold a bucket of beer, mash, mead or wine to completely small ones. Metal valleys were rarely decorated, since they were not placed on the table. The hostess just brought them to the table, pouring drinks into glasses and goblets, and immediately took them away. The wooden ones were very elegant. Favorite patterns were rosettes, twigs with leaves and curls, diamonds, and birds. The handle was made in the shape of a horse's head. The very shape of the valley resembled a bird. Thus, traditional symbolism was used in decoration. The wooden valley was placed in the middle festive table. It was considered tableware.

JUG– a container for liquid with a handle and spout. Similar to a teapot, but usually taller. Made from clay.

KRINKA– a clay vessel for storing and serving milk on the table. Characteristic feature Krinka is a high and wide neck, the diameter of which is designed to fit around your hand. Milk in such a vessel retained its freshness longer, and when sour it gave thick layer sour cream.

KASHNIK – a pot with a handle for preparing and serving porridge.

KORCAGA- this is a clay vessel large sizes, which had a wide variety of purposes: it was used for heating water, brewing beer and kvass, mash, boiling laundry. Beer, kvass, and water were poured into the pot through a hole in the body located near the bottom. It was usually plugged with a stopper. The pot, as a rule, did not have a lid.

A poker, a grip, a frying pan, a bread shovel, a broom - these are objects associated with the hearth and oven.

POKER- This is a short, thick iron rod with a curved end, which was used to stir coals in the stove and rake up the heat.

GRIP OR ROGACH- a long stick with a metal fork at the end, which is used to grab pots and cast iron and place them in a Russian oven. Usually there were several grips in the hut, they were different sizes, for large and small pots, and with handles of different lengths. As a rule, only women dealt with the grip, since cooking was a woman’s job. Sometimes the grip was used both as a weapon of attack and defense. The grip was also used in rituals. When a woman in labor needed to be protected from evil spirits, put the grip with the horns to the stove. When leaving the hut, she took it with her as a staff. There was a sign: to prevent the brownie from leaving the house when leaving the house, it was necessary to block the stove with a catch or close it with a stove damper. When a dead person was taken out of the house, a grip was placed on the place where he lay to protect the house from death. At Christmas time, the head of a bull or horse was made from a grip and a pot placed on it; the body was depicted as a man. When they came to the Christmas festivities, they “sold” the bull, that is, hit it on the head with an ax so that the pot would break.

Before planting the bread in the oven, coal and ash were cleared from under the oven by sweeping it with a broom. POMELO It is a long wooden handle, to the end of which pine, juniper branches, straw, a washcloth or a rag were tied.

With help BREAD SHOVEL Bread and pies were placed in the oven, and they were also taken out from there. All these utensils participated in one or another ritual action.

MORTAR- a vessel in which something is ground or crushed using a pestle, wooden or metal rod with a round working part. Substances were also ground and mixed in mortars. The stupas had different shapes: from a small bowl to high, more than a meter in height, mortars for grinding grain. The name comes from the word step - to move your foot from place to place. In Russian villages, wooden mortars were mainly used in everyday household life. Metal mortars were common in cities and among wealthy peasant families of the Russian North.

SIEVE AND SIEVE- a utensil for sifting flour, consisting of a wide hoop and a mesh stretched over it on one side. The sieve differed from the sieve in having larger holes in the mesh. It was used to sort flour brought from the village mill. Through it, coarser flour was sifted out through a sieve. In a peasant house it was also used as a container for storing berries and fruits.

The sieve was used in rituals as a container for gifts and miracles, in folk medicine as a talisman, and in fortune telling as an oracle. Water poured through a sieve was given healing properties, washed a child and pets with it for medicinal purposes.

TROUGH- open oblong container. It was made from half of a whole log, hollowed out on the flat side. The trough on the farm was useful for everything and had a wide variety of purposes: for harvesting apples, cabbage and other fruits, for making pickles, for washing, bathing, cooling beer, for kneading dough and feeding livestock. When turned upside down, it was used as a large lid. In winter, children rode it down the slides, like in a sled.

Bulk products were stored in wooden containers with lids, birch bark boxes and beetroot. Wicker products were in use - baskets, baskets, boxes made of bast and twigs.

TUES (URAC)- a cylindrical box with a lid and a handle-bow, made of birch bark or bast. Tues differed in their purpose: for liquids and for bulk objects. To make a container for liquid, they took chipped wood, that is, birch bark removed from the tree entirely, without cutting. Tues for bulk products were made from plastic birch bark. They also differed in shape: round, square, triangular, oval. Tuesa different shapes Each housewife had them in different sizes, and each had its own purpose. In some, salt was well preserved and protected from moisture. Others contained milk, butter, sour cream, and cottage cheese. They poured honey, sunflower, hemp and linseed oil; water and kvass. In the containers, food was kept fresh for a long time. We went into the forest with birch bark trees to pick berries.

Do not shake hands across the threshold, close the windows at night, do not knock on the table - “the table is the palm of God”, do not spit in the fire (stove) - these and many other rules set behavior in the house. Home is a microcosm in the macrocosm, one’s own, opposed to someone else’s.

A person arranges his home, likening it to the world order, so every corner, every detail is filled with meaning, demonstrating the relationship of a person with the world around him.

So we entered the Russian hut, crossed the threshold, what could be simpler!

But for a peasant, a door is not just an entrance and exit from the house, it is a way of overcoming the boundary between the internal and external worlds. Here lies a threat, a danger, because it is through the door that they can enter the house and evil person, and evil spirits. “Small, pot-bellied, protects the whole house” - the castle was supposed to protect it from an ill-wisher. However, in addition to bolts, bolts, and locks, a system of symbolic methods has been developed to protect the home from “evil spirits”: crosses, nettles, fragments of a scythe, a knife or a Thursday candle stuck into the cracks of a threshold or jamb. You can’t just enter the house and you can’t get out of it: approaching the doors was accompanied by short prayer(“Without God - not to the threshold”), before a long journey there was a custom of sitting down, the traveler was forbidden to talk over the threshold and look in the corners, and the guest had to be met at the threshold and allowed ahead of him.

What do we see in front of us when entering the hut? The stove, which served simultaneously as a source of heat, a place for cooking, and a place for sleeping, was used in the treatment of a wide variety of diseases. In some areas people washed and steamed in the oven. The stove sometimes personified the entire home; its presence or absence determined the nature of the building (a house without a stove is non-residential). The folk etymology of the word “izba” from “ heating" from " drown, melt." The main function of the stove - cooking - was conceptualized not only as economic, but also as sacred: raw, undeveloped, unclean was transformed into cooked, mastered, clean.

Red corner

In a Russian hut, there was always a red corner located diagonally from the stove, where we can see icons, the Bible, prayer books, images of ancestors - those objects that were given the highest cultural value. The red corner is a sacred place in the house, which is emphasized by its name: red - beautiful, solemn, festive. My whole life was oriented towards the red (senior, honorable, divine) corner. Here they ate, prayed, and blessed; it was towards the red corner that the headboards of the beds were turned. Most of the rituals associated with births, weddings, and funerals were performed here.

An integral part of the red corner is the table. A table laden with food is a symbol of abundance, prosperity, completeness, and stability. Both everyday and festive life of a person is concentrated here, a guest is seated here, bread and holy water are placed here. The table is likened to a shrine, an altar, which leaves an imprint on a person’s behavior at the table and in general in the red corner (“Bread on the table, so the table is a throne, but not a piece of bread, so the table is a board”). In various rituals special meaning was given to the movement of the table: during difficult births, the table was moved to the middle of the hut; in case of fire, a table covered with a tablecloth was taken out of the neighboring hut, and they walked around the burning buildings with it.

Along the table, along the walls - pay attention! - benches. There are long “men’s” benches for men, and front benches for women and children, located under the window. The benches connected the “centers” (stove corner, red corner) and the “periphery” of the house. In one ritual or another they personified the path, the road. When a girl, previously considered a child and wearing only an undershirt, turned 12 years old, her parents forced her to walk back and forth across the bench, after which, having crossed herself, the girl had to jump from the bench into a new sundress, sewn especially for this occasion. From this moment on, girlhood began, and the girl was allowed to go to round dances and be considered a bride. And here is the so-called “beggar’s” shop, located near the door. It received this name because a beggar and anyone else who entered the hut without the permission of the owners could sit on it.

If we stand in the middle of the hut and look up, we will see a beam that serves as the basis for the ceiling - the matitsa. It was believed that the matka is the support of the top of the dwelling, therefore the process of laying the matica is one of the key moments in the construction of the house, accompanied by the shedding of grains and hops, prayer, and refreshments for the carpenters. Matica was attributed to the role of a symbolic border between internal part hut and external, connected with the entrance and exit. The guest, upon entering the house, sat down on a bench and could not go behind the mat without the invitation of the owners; when setting off on a journey, he had to hold on to the mat so that the journey would be happy, and in order to protect the hut from bedbugs, cockroaches and fleas, something found from a harrow was tucked under the mat. tooth.

Let's look out the window and see what's happening outside the house. However, windows, like the eyes of a house (window - eye), allow observation not only by those inside the hut, but also by those outside, hence the threat of permeability. Using the window as an unregulated entrance and exit was undesirable: if a bird flies into the window, there will be trouble. Dead unbaptized children and adult dead people suffering from fever were carried out through the window. Penetration only sunlight looking through the windows was desirable and was played out in various proverbs and riddles (“The red girl is looking through the window”, “The lady is in the yard, but her sleeves are in the hut”). Hence the solar symbolism that we see in the ornaments of the platbands that decorated the windows and at the same time protected them from the unkind and unclean.